Welcome to the Escape Velocity Collection!

We are an opinionated group of friends reviewing all sorts of fantasy and science fiction media. Don’t forget to get to know the curators and visit our curated Collection, where we discuss the stories that never cease to transport us to another world.

Will you escape with us?

LATEST POSTS:

- Book written by Frank Herbert

- Published in 1965

- Part one in the Dune Chronicles

Paul, heir of House Atreides, and his family receive orders to move to the planet Arrakis, the rich desert world that produces the spice that allows for interstellar traffic, and take control of the fief from their arch-enemies, the Harkonnens. Though they sense a trap, his father’s honour does not allow them to defy the Padishah Emperor’s orders. In the struggle for the dominion of Arrakis that follows, Paul catches a glimpse of a terrible future that lies ahead if he does not act to change his fate.

Jop: Welcome to this in-depth, spoiler-free discussion of Dune by Frank Herbert, a classic science fiction book and the first installment in the Dune universe, which by now consists of multiple series. Our curator Peter added Dune to the Escape Velocity Collection, a series of items that we believe represent the absolute peak of what the speculative genre has to offer.

I challenged Peter to defend his addition to the Collection – why should every fan of speculative fiction pick up Dune immediately?

Defended By

PETER

Versus

JOP

Although the opinions on Dune might strongly differ among our curators, there can be no doubt about your love for this story. So, to start off – when did you first read Dune and what did it do to you?

I first read Dune somewhere halfway through high school. I remember asking my mum to recommend me a book to read in English, because I was practicing – back then, it was right on the edge of what I could understand. It was (and is) one of her favourites. I took the crumbling, well-used vanilla-smelling copy with the colourful sunset on the cover from the bookshelves and I absolutely loved it to bits. I’ve reread it at least three times since, and everytime I am afraid the magic will be gone, but it’s there every time.

There are two important reasons why Dune keeps working so well for me. The first is that Herbert respects the reader’s ability to figure things out on their own, and doesn’t feel the need to explain everything in the text of his novel. As a result, the strange world feels both natural – because the characters do not behave as if everything they do needs explanation – and mysterious – because some things hover just beyond the edge of explanation all the time, and I don’t think you’re intended to get them.

That leads into the second point: Herbert, for me, perfectly manages to write people that are just incredibly smart. Paul and Jessica, in the way they observe and analyse the world, are superhuman in a – to me – believable way. I know none of it is true, but for some reason, I constantly find myself in awe when reading about them. It makes me want to be like them in ways I have almost never experienced.

Worldbuilding

Without spoiling too much, when I was reading Dune, I can honestly say I was most impressed with its worldbuilding. Most of the story might take place on the inhospitable desert planet of Arrakis, home of the much coveted ‘spice melange’ drug, but there are many glimpses of a greater universe full of intricate politics. Arrakis itself is also well thought out, with a believable interpretation on how the ecology and cultures of such a place would develop and influence one another. I thought it was an original setting, though I myself have little frame of reference in the field of science fiction.

Is Dune’s worldbuilding one of the things that stood out to you, Peter?

I agree with you that the world the story of Dune takes place in is probably its greatest achievement. Herbert takes time to explore the ecology of Arrakis in detail: the difference between the different types of deserts, the habits of the few existing species of wildlife, the importance of conserving water in every thinkable process. On top of his ecology, he layers a fascinating local culture centred on the sand of the desert and conserving water. On top of that, he layers a high society culture of the Arrakeen elite, centred on wasting water and harvesting spice. And on top of that, he layers the politics of the Great Houses of the Landsraad, centred on intrigue and selling spice. Each of the layers influences the ones above and below it, and the whole takes place against a backdrop of a mysterious ancient history of human colonisation of the galaxy. The entire system functions very well, and, importantly, the worldbuilding is integral to the plot.

The world of Dune is so expertly crafted that I believe it is worth reading the novel exclusively to get to know Arrakis – I know people that even twenty years after reading the books remember little details on how the characters preserve water and how to walk across the sand undetected.

You already mentioned the fact that Herbert respects the reader’s ability to figure things out on their own. Though I certainly respect that sentiment in a writer, even I was somewhat overwhelmed by the worldbuilding infodump you get in the first 150 pages of the story. If you’re not careful, you’ll find yourself lost in the terminology appendices at the back of the book after every two sentences.

Even though the quality of the worldbuilding is outstanding, one could argue it’s clumsily delivered. So much so even that it scares off (novice) readers. Do you think this is a fair assessment?

Well, I’ll give you that Dune has a steep learning curve, but I strongly disagree with the notion that Herbert infodumps. Rather, the worldbuilding is a continuous trickle (perhaps to some readers, more of a flow than a trickle) that constantly keeps you guessing. But that’s the point! I believe that Dune is intended to be a mysterious book. Don’t go look up terms in the appendices – you’ll figure it out by yourself in a couple of chapters. Paul, our main character, is dumped in a world he knows very little about, and is constantly learning – and so is the reader. Accept that you might not understand everything immediately – you’re not intended to. And it is all the more satisfying if you end up ‘getting it’ on your own.

No, I cannot deny that Dune is not exactly a light read. There are a lot of complex conversations, a lot of complex politics, a lot of original worldbuilding. But I would argue that the worldbuilding is actually presented in a rather subtle manner. You’ll need to pay attention, but it is one of the most well-constructed science-fiction books I’ve ever read, and entirely worth the effort it takes to learn about its universe.

Something I specifically noticed about Dune’s worldbuilding, is the incorporation of Middle-Eastern and Asian inspired elements, especially in regards to the religions. As I’m mostly familiar with fantasy worldbuilding, in which Christianity and ancient pantheons are commonly used as the basis of self-built religions, I thought Herbert’s choices were interesting.

However, I’ve come to understand there are some who criticize these same aspects. These people accuse Herbert of religious appropriation and orientalism, for example describing his depiction of the desert-dwelling Fremen warrior culture as harmful (muslim) terrorist stereotypes.

On the other hand, others praise Herbert for the clever and positive way he’s included non-Western elements, pleasantly surprised to recognise things from their own cultures in a science fiction setting.

What do you think of this discussion?

I think it is important to place Dune in the time in which it was written – the first half of the 1960s. I’ll skip the history lesson, but if I understand correctly, the pervasive (and toxic) link between ‘muslims’ and ‘terrorists’ in modern culture dates from after the 1967 Six Day War between Israel and its neighbours, when several anti-Israeli terrorist organisations sprang into life. I cannot deny that that link exists today, but at the time, I feel like Dune would more likely be read in the tradition of Lawrence of Arabia (and, admittedly, all the colonial ickiness that comes with that) than 9/11.

That said, it is true that the Fremen culture is based on a relatively western orientalist interpretation of Middle-Eastern (or West Asian, if that’s your preference) and Persian culture. Cultural sensitivity and the woke brigade weren’t a thing sixty years ago, and it shows.

Herbert kind of wears this on his sleeve, though – he writes of cultural/religious amalgamations such as Buddhislam and the Zensunni faith, the result of the mixing of Asian cultures throughout the centuries-long colonisation process of the Galaxy. In his view religious and cultural identities are constructed (sometimes literally and deliberately), and the cultures of the various ethnic groups in the Dune-universe are (to some extent) intended to be caricatures of their origins on Earth.

Herbert does still use the Arabic-coded Fremen as an ‘other’, a group that is intended to be alien to western audiences. And in that sense we can’t really applaud him for his progressive writing. But given the time he was writing in, I think that his positive, human portrayal of the Fremen (and, compared to his contemporaries, women) should be grounds to forgive him his sins.

Characters

You already spoiled some of your thoughts about Dune’s characters, namely that you enjoy how they are written so much that you’d almost like to be them. For people who know how picky you are about characters in general, I believe this is an incredible telling compliment.

Is their intelligence the only reason you were attracted to Paul and Jessica as main characters? And what were your thoughts on the other POV-characters? In your opinion, do they hold up next to Paul and Jessica?

The intelligence and Bene Gesserit training of Paul and Jessica make them fascinating characters to read about, but they are also interesting because they are portrayed as primarily rational characters, inwardly very observant of their emotions and the actions caused by their emotions. This is a welcome change from characters with a lot of inner monologue in most books, who have a tendency to be very emotionally driven. Plus, they have a beautiful awareness of their fate that puts each of their actions in a different light.

None of the other POV-characters are as well-defined as Paul or Jessica, but I feel Herbert has made the right choices in picking his viewpoints, allowing the reader to experience each of the pivotal moments in the saga up close. Their chapters give great little insights into the thinking of some of the other characters and factions.

Circling back a little to the smartness and strong rationality of some of these characters, you’d expect that they’d make less crucial wrong decisions than the emotionally driven characters in most other stories. Interestingly enough, this is not the case. Dune’s characters still make these kinds of mistakes, not because they are too emotional though, but because of the opposite: they don’t dare to trust their intuition. It’s an original divergence.

Plot

Every synopsis and flap text of Dune paints a picture of a vengeful revolution story full of politics, a captivating premise for a plot. Quite early in the story, however, it occured to me that many plot elements are spoiled in advance by the codices at the start of each chapter.

Do you think these codices undermine the plot’s strength?

No, on the contrary, they add to it! I can’t quite say, ‘Dune is not about the plot’, because that wouldn’t be true. The plot is an important part of what makes Dune great. But the plot of Dune is not about surprising the reader with clever twists. The reader is supposed to unravel the mystery of how the plot will get to where it has announced it will go. In a way, this mirrors Paul’s own experience: he gets told his fate, and the rest of the story is about figuring out how it will unfold – and fighting it.

And this is a conscious choice on Herbert’s part. You’re supposed to know how it will end, and to hope against hope. The codices and the POV-chapters from the perspective of the ‘bad guys’ allow Herbert to showcase the complexity of the world and the clever plans of all factions to the reader. It makes for a different reading experience, watching a tragedy play out from every angle and seeing the struggles of the characters caught in the flow.

I think Dune would work far less well if you wouldn’t have the ‘spoilers’ the story gives you, because a lot of the behind-the-scenes cloak and dagger would be lost on you.

There are a lot of instalments (several dozen, give or take) in the Dune-universe, and Dune itself is only the first book in a trilogy. It’s somewhat remarkable you’re only adding Dune to the collection. Is it a conscious choice that you’re disregarding the rest of the series?

So, the honest (possibly embarrassing) answer is, I have only just read the second part, Dune Messiah, in preparation for our conversation here. And of course, I haven’t lived underneath a rock so I know more or less what will happen beyond the second instalment too. But one of the reasons Dune works so well for me is the mystery that permeates from the pages. And I don’t want to shatter that by learning too much about the world. Dune Messiah is a good book, and I think that people who really enjoyed Dune are going to like reading it too and seeing where the story goes. But the scene is already set, so there is only little of the amazing worldbuilding that Dune has. And the book makes explicit some of the things that you might have guessed at the end of Dune, but you felt clever for figuring out on your own. Overall, it’s good, but simply not on the same level, and not necessary to deeply love Dune.

Age

Dune is universally seen as a science fiction classic and has been of a major influence on the genre. Though this is impressive, it comes with the fact that the story dates from 1965. That’s a respectable age of 56 years.

We’ve already touched on this a little. In your own words: cultural sensitivity wasn’t a thing back then. However, everyone that has experience with high school reading lists might think of some other pitfalls that could come with books that old, such as stuffines and extreme wordiness. Can these traits be applied to Dune, or is the prose as flashy and fast-paced as people have come to expect of modern science fiction?

Dune is not a light, quick, read. A lot of the tension in the story is built up over long conversations between people fencing with words, not swords. Herbert has a tendency to be very descriptive (which I love), and to use relatively flowery language (which I love). It’s not snappy in the way that some action packed modern novels are. But it’s also not Asimov! Sure, some of the conflict will be narrated from a distance. But if there is fighting, you’re sure to catch at least some glimpses of steel-on-steel. Blood will flow from the pages before the tale is over.

I don’t think that pace or tension arcs are this books traps – it’s rather getting lost in the complex plot, politics and world building, or not buying into the Bene Gesserit training or the carefully constructed conversations. Dune takes itself rather seriously (which I love!), and if you do not, it’s unlikely you’ll reach the end.

Conclusion

In summary, Dune is an intricately crafted, multi-layered story with some excellent worldbuilding, justly a praiseworthy science fiction classic. Although this book was ultimately not for me, even I can appreciate the many unique ideas it has to offer. In fact, despite our thoroughness, there are still many aspects of the story we have left undiscussed, such as Dune’s many intriguing themes.

Peter, is there something you’d like to add before we close off?

We’re sadly running out of space to discuss everything there is to discuss – most importantly the themes and threads of religion and fate that run through the books, but also the interesting way in which Herbert mixes fantasy elements into his science fiction setting, Herberts ideas on ‘hard men’ and ‘soft men’, fascinating elements of world building like the Butlerian Jihad and the origin of Mentats…

Maybe what I want to say is: there is so much to find in Dune, that I feel that almost anyone can find a theme or a layer or an element to enjoy. And if that is the case, then anyone that professes to love science fiction should at the very least give a genre-defining masterpiece such as Dune a shot.

That’s it for now folks! Go read Dune if you haven’t already, and soon we’ll be back for another addition to the Collection!

- Book written by Frank Herbert

- Published August 1965

- First part in the Dune Chronicles

Paul, heir of House Atreides, and his family receive orders to move to the planet Arrakis, the rich desert world that produces the spice that allows for interstellar traffic, and take control of the fief from their arch-enemies, the Harkonnens. Though they sense a trap, his father’s honour does not allow them to defy the Padishah Emperor’s orders. In the struggle for the dominion of Arrakis that follows, Paul catches a glimpse of a terrible future that lies ahead if he does not act to change his fate.

Right out of the gate, I’m going to go ahead and say that I think Dune is one of the very best science-fiction books that was ever written. It is one of my favourite books of all time, and you can read my discussion with Jop on why I’ve added it to the collection here. I’ve said most that is to be said there, but some of it bears repeating.

In short, Dune is such a great book because of three main reasons. First, Herbert respects his reader’s ability to figure it out on their own. There is a lot of worldbuilding in Dune (more on that later), but Herbert doesn’t feel the need to explain all of it as soon as it becomes relevant – instead, things are slowly revealed as Paul, the main character, gets more and more familiar with the new planet he lives on. This creates a true sense of mystery, and learning alongside Paul, that many modern works have replaced with clever ways to have everything explained upfront.

Secondly, I really love the way the main point of view-characters, Paul and his mother Jessica, are presented: as incredibly smart, rational, and introspective. Dune is a novel with very well fleshed out characters that is not all about emotional drama, and that feels unique.

Finally, and most importantly, Dune has the best worldbuilding in the speculative genre, bar perhaps The Lord of the Rings. And unlike many other fantasy or science fiction works, the worldbuilding isn’t just there to be interesting, it is fundamental to the plot. Herbert has created a believable ecology, on top of which he layered a fascinating desert culture and a contrasting elite culture, on top of which we see the planetary politics, which are, in turn influenced by interplanetery forces, etc. Each of the layers is interesting in its own right, and the whole combines to form one of the best novels I’ve ever had the honour of reading. And I haven’t even touched on themes of religion and fate that run through the story and bind it all together.

Now, Dune isn’t for everybody. It is not a light read. It requires patience, and attention, and a lot of straining to follow along with the clever conversations of smart people full of hidden meanings that sometimes seem just out of reach. If that sounds bothersome to you, then perhaps Dune won’t be to you what it is to me. But if you feel tempted – please, give it your best shot. It is all totally worth it. Dune is just so incredibly good. So. Incredibly. Good.

Really. Go read it.

This is one of Peter’s all-time favourite books, so by all means I feel I should have liked it too. Alas, I fear I’ll break his heart with my review, for I had trouble even finishing Dune.

Dune follows a ducal family as they, entangled in political plots, try to settle on an inhospitable planet and later rise in rebellion against their enemies. Paul Artreides, the only son and heir of house Artreides is the main protagonist. Other POV-characters include his mother Jessica, several (loyal) followers, and the antagonists.

Although the premise of the plot is promising, I would not say it is in any way one of the strong points of this story. Indeed, most of the plot points are consistently spoiled by the codices at the start of each chapter. Such a foreshadowing technique might have been interesting if the characters could carry the story on their own, but in my experience Frank Herbert never really succeeds in making his characters well-rounded or relatable. Some of the characters are superhumans who experience emotions in different ways than normal humans are used to, an interesting concept, but even in these cases the characterization seemed to lack.

It is possible I could have overcome the above listed shortcomings, had it not been for Frank Herberts writing style. I found there was too much “tell” instead of “show”, which occasionally even resulted in overwhelming info dumps. Although I recognize his prose is not at all bad, his style was not a fit for me.

All in all, Dune’s strongest elements were its worldbuilding (well thought out and comprehensive) and the underlying themes. Can one change their fate? What does it mean to be human? What is the essence of religion? These are just a few of the many questions raised in the story, in addition to multiple environmental issues. I appreciate how Frank Herbert handles these major themes, even though the rest of the book didn’t really appeal to me.

In conclusion, I understand how Dune came to be an influential classic in its genre. However, I would not quickly recommend it to readers who enjoy a gripping plot and/or relatable characters.

Nope, this book is most definitely not for me. Apparently this is considered a classic. However, the outrageous amount of unnecessary new words that are used in every sentence makes it a very hard task to get through. I listened to the first quarter of the story as an audio-book. Pro: you can ignore all the words you don’t know. Con: every time the evil guy starts to plot his evil political scheme, my brain automatically drifts away.

After that I read some more chapters in a real book. I was curious to see the new world they were travelling to. I never got to see it, after reading 300+ pages I was completely done. They never left the spaceship.

Like I said. This book is not for me. If you are looking for a book that is accessible, look further.

Tagged:

- Movie directed by Tim Burton

- Based on Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children by Ransom Riggs

- Starring Eva Green, Asa Butterfield, Chris O'Dowd, Allison Janney, Rupert Everett, Terence Stamp, , Ella Purnell, Judi Dench and Samuel L. Jackson

- Released in 2016

- Runtime: 127 minutes

- Standalone

Haunted by mysterious events in his grandfather’s life, Jacob travels to the Welsh island of Cairnholm to learn the truth of his grandfather’s old stories. Here, he finds the ruins of an orphanage, Miss Peregrine’s home for Peculiar Children. Who were the children who lived in this house? What was so peculiar about them? And why were they hidden away on the island?

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is the kind of movie that constantly keeps you guessing about what’s going to happen, and I liked that. I entered without any foreknowledge or expectations and was quickly ensnared by the plot’s mysteries and the movie’s suitable dark atmosphere (as can be expected from Tim Burton’s cinematography). And even later on in the story, long after all the mysteries were unraveled, I was engrossed with the marvelous (action) scenes that were presented.

I suspect the original novel has a lot more depth (allegories of the Holocaust?) than can be transferred into a movie, both in terms of characters and plot. This becomes somewhat apparent at times. However, the (child) actors deliver an excellent performance in their limited amount of screen time. I also quite liked Samuel L. Jackson’s portrayal of the antagonist.

Though Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is supposed to be a family movie, I wonder if younger children would enjoy the plot, which can be somewhat slow or even confusing at times. Also, be prepared for some minor gruesome visuals.

Tagged:

- Graphic novel written and illustrated by Tillie Walden

- Published October 2018

- Standalone

‘On a Sunbeam’ tells the story of Mia, who joins a space crew that rebuilds old structures. While she adapts to this new life, she reflects on her youth and a long-lost love.

Robin recommended this graphic novel to me, and she was totally right. I enjoyed it. Its mysterious atmospheres and soft yet complicated characters truly transported me to another world.

When it comes down to it, the stories of Mia and the other characters are actually quite simple. The main plot revolves around a love story and a traditional quest. Many aspects of the subplots and the intriguing worldbuilding are never explained. In this sense On A Sunbeam is more of a character-driven experience than a story. An enchanting experience enhanced by beautiful art.

I once again turned out to be a hopeless romantic, as I felt for all the (sapphic) relationships throughout the story. It was also cool to see a non-binary character play a large role in the narrative. Come to think of it, I don’t believe I’ve seen any male characters come along at all. I can’t necessarily say I missed them, though.

On a Sunbeam is an excellent read for people who yearn for a more optimistic and magical world in which a sense of wonder may remain.

On a Sunbeam is an endearing story that puts me in mind of a Becky Chambers novel. The drawing style is very beautiful and the use of a limited colour palette adds a lot to the mysterious atmosphere of the book. The main ‘baddie’ did feel a little forced to me, like she was only put in so that the protagonists could have someone to shout at about why its important to use people’s correct pronouns. This sentiment itself is a really important one though, so I can forgive the slightly clumsy way in which it is included in the book. Overall I just really enjoyed this story and would definitely recommend it to young adults and older audiences alike.

Tagged:

Time to get to know the curators from the Escape Velocity Collection! How? By asking them the questions that really matter! Let’s see what our curators have to say…

This week’s question is:

Who is your favourite mentor character from Fantasy or Science Fiction media?

The ‘Mentor Character’ is one of my favourite tropes, so this was not an easy choice for me. In the end, I settled on Elodin from Patrick Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicles. What I like about Elodin is that he is kind of a wild card. He is not the comforting old mentor who you can count on to know what is best and to make wise decisions. Instead, he is chaotic, undependable, and at times quite an ass. However, it is clear that there is much more ‘method to his madness’ than Kvothe gives him credit for. Above all, I just think he is very funny and the scenes in which he features are some of my favourite parts of the books.

This might be a case of recency bias, but I just read A Memory Called Empire and I loved the way Martine wrote Yskandr Aghavn as a mentor character. There were so many interesting twists to the way the trope was played! Some spoilers below.

Firstly, I liked that Yskandr wasn’t a separate character, but rather a force that taught Mahit from inside herself. Second, I loved that after the set up making the reader expect him to play a typical mentor role, he disappeared when Mahit needed him most – leaving her all alone in the hands of Three Seagrass, who was an equal more than a mentor. And to top it all off, when Yskandr finally returns, Mahit has already completed her journey and no longer needs him the way she did. What a beautiful way to subvert a common trope!

Jawbone O’Shaughnessey. If you’ve watched Dimension 20’s Fantasy High, you’ll know Jawbone was once a washed up, drug-dealing werewolf. He’s a wolf of the world, baby! No one knows what it’s like to go through it more than him, which is what makes him such an amazing guidance counselor. What I like most about Jawbone is what he represents: He’s not a huge character when he is first introduced. He’s just some random werewolf without health insurance the Bad Kids meet in a bar brawl. Still, they gave him a chance (albeit mostly jokingly) by telling him that their high school was looking for a guidance counselor, and because of that one conversation, he suddenly became quite a major character in the story, essentially acting as a father figure to Adaine, Kristin and Fig. It shows us that the people who help us grow the most in life are often not the ones we expect to do so.

I thought long and hard and then came to the conclusion that I actually don’t really like the concept of mentor characters? Instead, I prefer characters who have to figure everything out themselves. The ones who defiantly go off and do their own thing. Bonus points when those things go horribly wrong the first time and they have to overcome their own struggles, becoming wiser in the progress. To me, this is a much more interesting narrative than some other character guiding them to do the right thing. So I guess my favourite mentor characters are protagonists that are their own mentor character. Roald Dahl’s Mathilda is the first that comes to mind. I love how she finds her courage by going her own way.

I would say The Lord of the Rings’ Gandalf, at least as he is portrayed by Sir Ian McKellen in Peter Jackson’s movies.

At first glance, this might seem somewhat of a boring opinion. In many ways, Gandalf is the mentor archetype from which most other mentor characters are derived: a wise, old wizard, who eventually ‘dies’ to allow the development of the other characters. However, most of these Gandalf knockoffs miss Gandalf’s depth. Yes, he is old and wise, but at the same time he’s never quite certain of his own deeds and counsel. At times he makes mistakes. He lacks confidence – and sometimes even hope – but strives to do his best anyway and help others do the same.

Gandalf is imperfect but therefore human. And that is precisely why he is a great mentor.

Man, I had a hard time thinking of a good one, but I think I have thought of a nice duo: Burrich in the Farseer Trilogy of Robin Hobb and Hagrid in the Harry Potter series of J.K. Rowling. They are goodhearted men who (reluctantly) watch over two children who have no other adults to take that role. As Fitz and Harry grow older, their relationship with their ‘fosterfathers’ changes. The older men marvel at the personal growth of the young ones, try to protect them, get angry when they do something stupid, argue to tears, make up and become friends. Although I must say, the relationship between Burrich and Fitz has pulled my heartstrings more (read: is more painful) than that between Harry and Hagrid.

That’s it: another soul-searching question answered!

Still curious? Visit each curator’s page to see what they’ve recently been up to!

Check out our reviews of the media recommended in this post here:

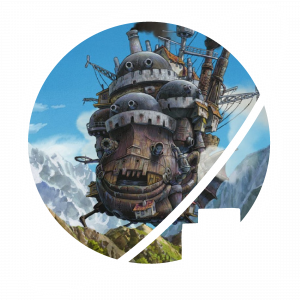

- Movie directed by Hayao Miyazaki

- Based on Howl's Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones

- Voiced by Jean Simmons, Emily Mortimer, Lauren Bacall, Christian Bale, Josh Hutcherson, Billy Crystal

- Released 20 November 2004

- Runtime: 119 minutes

Set against the backdrop of a destructive war, this is the story of young hatmaker Sophie, who is cursed by an evil witch to look like an old woman. Being unable to speak of her curse because the magic forbids it, she finds work in the home of a mysterious wizard in the hope that he will someday be able to lift the spell.

I think that this movie is generally well loved and many may find three and a half stars to be an injustice. Howl’s Moving Castle is one of those pieces of media, however, where a single star rating isn’t representative of a more complex opinion.

The visuals of this movie are an easy five out of five, as are most of Studio Ghibli’s works. Especially the backgrounds of the cities and landscapes paint such a beautiful picture of the world that you want to live in it despite the ongoing war. The actual moving castle is also beautifully designed, to the extent that it almost becomes a character itself. The movie is full of breathtaking shots and iconic imagery and worth watching for that alone.

The trouble is in the latter half of the story. I have to admit that, to my shame, I did not read the book first. But as a result, I could not make sense of the final maybe half an hour of the movie. There are no blantant plot holes or anything along those lines. The story just becomes… a hazy blur from scene to scene. There is a long string of emotional beats, ups and downs, highs and lows… but I walked away wondering how all of that magic worked and I still don’t quite understand how the story resolved in the end. Perhaps it is telling that the 4th Google search suggestion for ‘Howl’s Moving Castle’ is ‘Howl’s Moving Castle explained’.

So Howl’s Moving Castle is a bit of a mixed bag for me. As an animated feature, it looks absolutely amazing. Gorgeous. As a story, it falls flat. If I could rate them separately, the movie’d probably get 5 stars for it’s looks, 2 for its plot. On average, that’s about 3.5 – a solid recommendation, but not necessarily from the top shelf. Really, whether or not you should watch this movie is entirely up to what you are looking for. Just want to sit back, relax, and enjoy the view? Great, go ahead! Want to get wrapped up in a cool story of magic and war? Eh, maybe there are better candidates out there.

I was super late to the game on Howl’s Moving Castle. Like, well past the theme music being the soundtrack to EVERY cottage core video on the internet ever. You know how some things are super popular but you just can’t be bothered to check them out? Yeah. Guilty as charged.

I love this movie. I’ll be honest, it’s mostly aesthetics for me. Some movies just make you feel something.

Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle is based on the book by Diana Wynne Jones. When I was a kid, I read a lot of her novels. My dad would go to the library and just bring me a stack of books, and I’d read them all in time for him to go back and bring me a new stack. I don’t remember much about the actual stories, but I definitely remember the feeling of being transported to a different world – something I also feel very strongly while watching this movie.

While I agree with Peter on the story being confusing, I do think that not every story has to make sense. These days, a lot of stories get bogged down with unnecessary explanations of, for instance, how the magic system and the world work. There’s a whole bunch of people who love poking holes in stories just because they leave a couple of things to the imagination.

So sure, the story gets a little confusing at times, still I’m incredibly glad that the cottage core kids cyber bullied me into finally watching this film.

See also:

Collected: Dune by Frank Herbert

COLLECTION: Paul Atreides and his family move to the desert world Arrakis, to take control from their arch-enemies. In the struggle for the dominion of Arrakis that follows, Paul catches a glimpse of a terrible future that lies ahead.

Review: Dune – Frank Herbert

First part in the Dune Chronicles – Paul Atreides and his family move to the desert world Arrakis, to take control from their arch-enemies. In the struggle for the dominion of Arrakis that follows, Paul catches a glimpse of a terrible future that lies ahead.

Review: Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Tim Burton

Haunted by mysterious events in his grandfather’s life, Jacob travels to the Welsh island of Cairnholm to learn the truth of his grandfather’s old stories. Here, he finds the ruins of an orphanage, Miss Peregrine’s home for Peculiar Children. Who were the children who lived in this house? What was so peculiar about them? And why were they hidden away on the island?

Review: On a Sunbeam – Tillie Walden

On a Sunbeam’ tells the story of Mia, who joins a space crew that rebuilds old structures. While she adapts to this new life, she reflects on her youth and a long-lost love.

Curator Question: Mentor Characters

Our curators discuss some of their favourite Mentor characters from Science Fiction and Fantasy media.

Review: Howl’s Moving Castle – Hayao Miyazaki

Young hatmaker Sophie is cursed by an evil witch, and, being unable to speak of her curse because of the magic, finds work in the home of a mysterious wizard in the hope that he will someday be able to lift the spell.